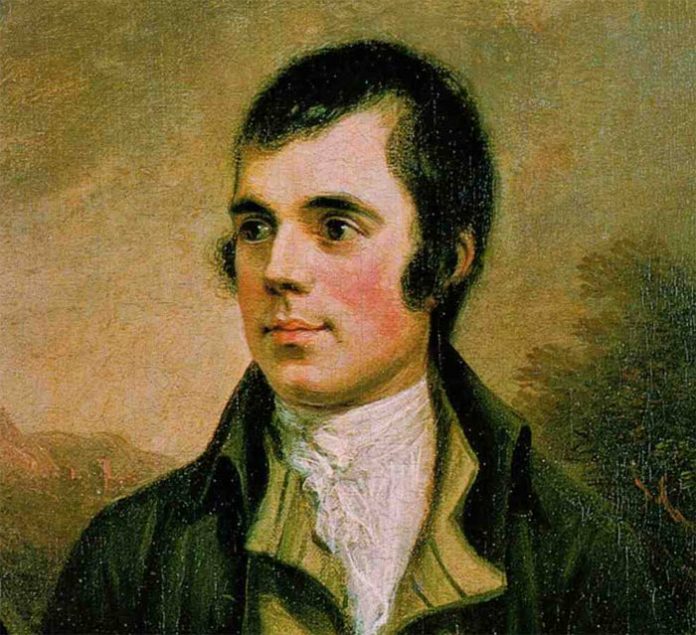

Scientists have for the first time analysed the ingredients the Scottish bard Robbie Burns used when he made his own ink.

Their study, which means that forgeries can now be easily identified, suggests that Burns wrote many of his poems using a mixture of old ale, carbonised elephant tusk, lard and sulphuric acid, all of which were readily available in 18th-century Scotland.

A team at the University of Glasgow analysed the ink and paper of both authenticated and forged Robert Burns’ manuscripts to produce a ‘Support Vector Machine classifier’ that could accurately distinguish true Burns handwriting from the fakes.

The scientists were also able to distinguish which inks Burns used to write each of his poems, whether it be ivory black, iron gall or a mixture of the two.

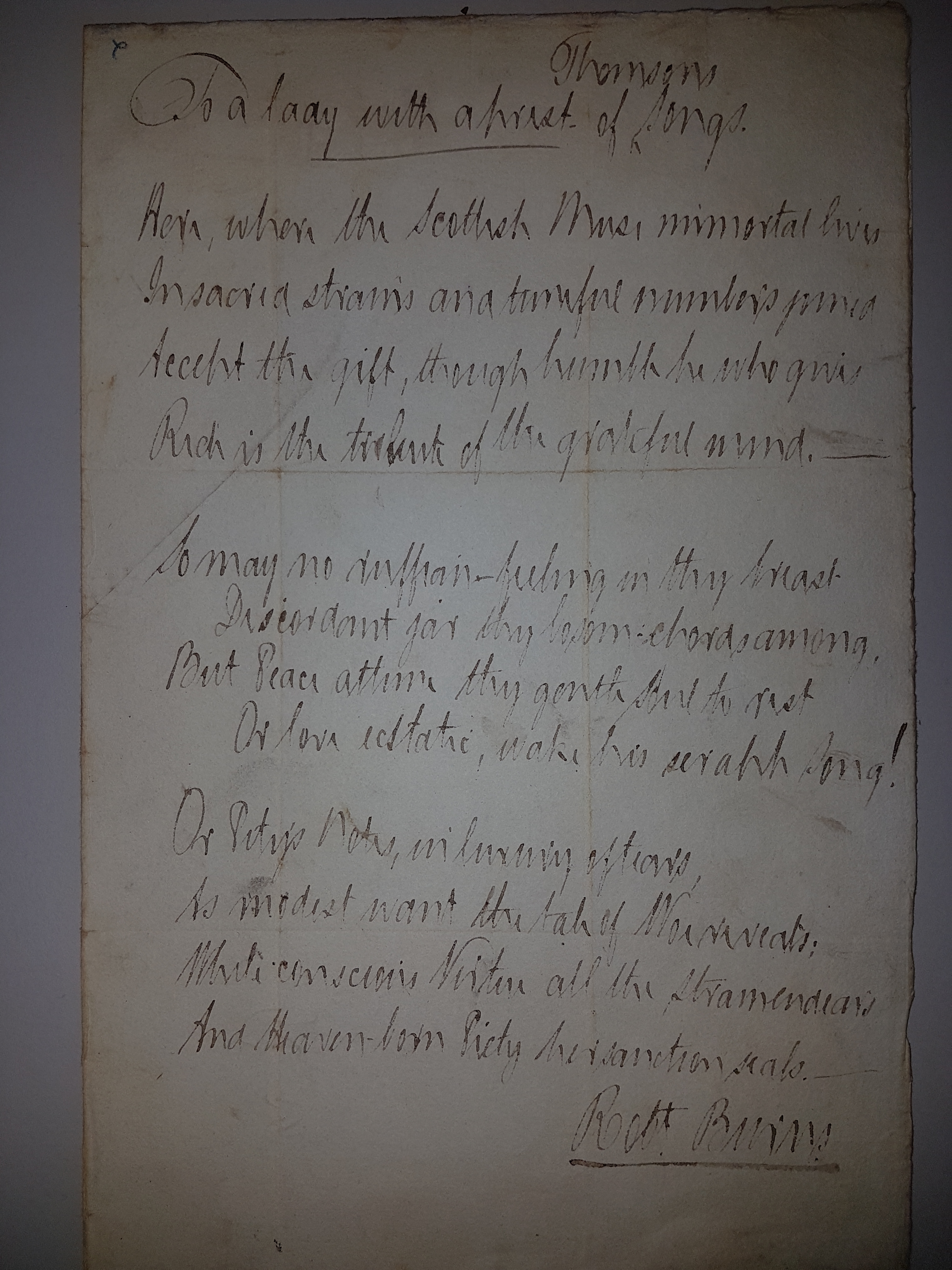

With the help of Burns collector Dr William Zachs, the team were able to look at originals and fakes to ascertain the type of ink used, helped by a handwritten book owned by Dr Zachs which contained recipes for all sorts of liquids, including inks.

In total, the team tested 12 documents; three real Burns’ documents selected from different periods of the bard’s life, and nine fakes from the 1890s by notorious forger Alexander Smith.

The scientists were able to lift ink from the copies using a simple pipetting process that could be performed outside the laboratory, and that crucially did not visibly damage the original material. Tests were initially performed on one of Alexander Smith’s handwritten 150 year old fakes before being performed on real Burns’ material.

Details of the ink and paper from the 12 documents were analysed, the data gathered and machine-learning algorithms were used to develop a classifier for the documents. The classifier, or ‘Support Vector Machine’ could then be used to help predict real or fake Burns’ manuscripts.

Sixteen significant differences were found distinguishing the Burns and Smith manuscripts. Significant differences between the inks and paper were also detected in Burns manuscripts.

In the The Holy Fair manuscript by Smith and in the letter written by R. Burns, the team detected iron gall ink, and in the Dainty Davie poem by Smith, they detected the presence of ivory black. In the Five Carlinsmanuscript by Burns, they detected both ink features, demonstrating that Burns, as was common at the time, mixed inks to obtain a desired lustre and consistency in his writing.

Dr Burgess said: “Through this technique we now know some things about Burns that we never knew before. However we’re particularly excited about that fact that we have a new way of providing more evidence for a fake or a real manuscript if one turns up, and we have a technique that we can apply to any manuscript to gain more information about it.

“The simplicity of the sample preparation method we used means that the sampling can be easily performed at the site where the manuscripts are stored, which in turn could make it an ideal technique for auction houses to confirm authenticity.

“In future, we’d like to analyse as many historical documents we can, so that we can begin to build a database of inks and manuscripts.”

Professor Carruthers said: “In terms of Robert Burns there has been a huge historic industry in forgery and fakery, and he is not alone in this. It is very exciting that we’re creating an authenticity tool that will have wide implications for scholars, libraries, archives, auction houses and collectors. This appliance of science to the physicality of culture is a crucial development.”