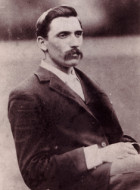

It is one hundred and fifty years today that Sebastian de Ferranti was born and to mark the anniversary, the Museum of Science and Industry are releasing two unseen photographs of his as a child.

One of him as a ten month old baby and one taken on his 16th birthday, both taken by his photographer father in his Liverpool studio.

The images come from the Museum’s collection of over 1500 Ferranti-made objects plus original letters, company records, his business archives and even letters from his workers.

Archivist, Jan Shearsmith, who discovered these images also uncovered letters from the period prior to and just after Ferranti’s 16th birthday.

From reading these letters, it transpires that while still at school, Ferranti had attempted to solder two broken pieces of carbon together using molten lead which had led to a small explosion. This had caused him some minor injuries to his face.

His father wrote to the Father Superior asking him to be banned from doing any hot metal work. This ban lasted for some time. Further letters reveal a desperate Ferranti pleaded to have this “revoked”. In one letter he wrote the following: “What is life to a person who has lost (even if it be not for long) what they love best”.

As Shearsmith, who has been cataloguing the Ferranti archive at MOSI for over 7 years says, “Talk about emotional blackmail!”

Sebastian was born in Liverpool in 1864 to an Italian father and English mother, who was a concert pianist and from a young age, showed a remarkable talent for electrical engineering.

The newly released image taken on his 16th birthday, shows a boy who by the time this milestone had been reached – had already built an electric bell system. Not just wiring together the system but, also making the components to go with it. This was by hand and without the aid of instructions or manuals. He was simply working from patents.

Armed with what was a great deal of money in the 1880’s he set up a business in London designing electrical equipment. These were the early days of electricity manufacture and distribution and Sebastian arrived when the debate about the best way to deliver electricity was at its height.

The alternatives proposed were Direct current (DC) ,a system backed by no greater a figure than Thomas Edison and Alternating Current (AC) whose main supporter was a gentlemen by the name of Nikola Tesla and supported by an American company,whose name would soon be associated with Manchester, Westinghouse.

The system of alternating current would eventually be the standard for producing electricity around the world and to this day has never been superseded.

The war of the currents was fought between Edison and Tesla with Edison insisting that it was too dangerous. The only casualties in the battles were the animals Edison publicly electrocuted with Tesla’s high voltage system to prove his point. The early victims were dogs and cats, but Edison eventually electrocuted an elephant named Topsy.

Alternating current won in the end because it could be transmitted over longer distances without losing energy, Edison’s system would have required generators at the end of every street. Ferranti’s skills, meanwhile were to overcome the problems with the alternating current, the Deptford station would be producing high voltage electricity which would be stepped down by transformers as it reached the customer.

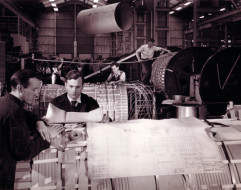

Ferranti arrived in Hollinwood in 1896 searching for cheaper land and cheaper labour to establish a new factory which would not only be producing electrical engineering machinery but would embrace mechanical engineering, the design and manufacture of textile machinery, and instrumentation.

By 1910 the company would have 176 patents on everything from alternators through to high-tension cables, circuit breakers, transformers and turbines.

Archivist Jan Shearsmith explains: “The contributions Ferranti made to engineering both during his lifetime and beyond are immeasurable. His factory closed down in 1994 after over 100 years of innovation and enterprise. But the legacy continues. What is all the more remarkable is that he invented and discovered so much at such a young age. His first invention was an arc light for street lighting, originally developed when he was just 15 and it was in his early 20s when he first discovered the economic benefits of creating power stations.”

Curator of Science & Technology, Alice Cliff, continues: “Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti was one of the foremost electrical engineers of his time. It is a privilege to have found these personal family photographs in our vast Archive collections here at the Museum of Science and Industry”.

The Ferranti Collection was presented to the Museum of Science and Industry in 1996 by Sebastian de Ferranti, grandson of the company’s founder, and the company’s administrative receivers. Ferranti Ltd gathered together its company archive in 1960 and employed an archivist until 1990. It also built up a collection of its products, partly with the support of current and former employees who donated consumer products such as clocks and radios.

Full details of the Ferranti collection are available online:

http://www.mosi.org.uk/collections/explore-the-collections/ferranti-online.aspx