“The vast progress that you have made in the short space of twenty months fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed and that the erasure of that foul blot on civilisation and Christianity, chattel slavery during your Presidency, will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honoured and revered by posterity.”

The words of Abel Heywood echo from the statute that gazes across Brazennose Street.

It is thought of as a somewhat Mancunian legend, Lincoln supported by the City of Manchester, in his fight against slavery, despite the hardships that his blockade of America’s southern ports were having on the cotton industry and as the rumblings of past and future battles with Liverpool, a city that was helping to build the confederates warships and whose city was founded on the profits of the slave trade.

John Bright, who had been swept aside by a patriotic vitriol of the voters of the city over his opposition to the war in Crimea, based partly on his Quakerism and a mistrust of Turkish motives, was a great admirer of the American president.

When Lincoln was felled by the bullet of John Wilkes Booth, amongst his possessions in his pocket was a letter from Bright, a testimonial for his re election in the forthcoming vote.

Whilst Britain had remained neutral during the civil war, Bright remained firmly on the side of the North supporting the civil rights movement for the freedom of the slaves.

This, despite seeing the Northern economy devastated by the war with dramatic falls in the supply of cotton. Bright’s own mill was forced to close during the cotton famine, only to be alleviated when supplies from India started to arrive, supplies that would eventually lead to the downfall of the industry.

Bright had many invitations to travel to the USA, and although he was never to take them up, his star shines in the White House to this day, a bust rediscovered from one of the alcoves was placed in the entrance hall by Jackie Kennedy and as Obama began to dismantle the special relationship by removing all things Churchillian, Bright’s photo by all accounts remains in the Oval Office.

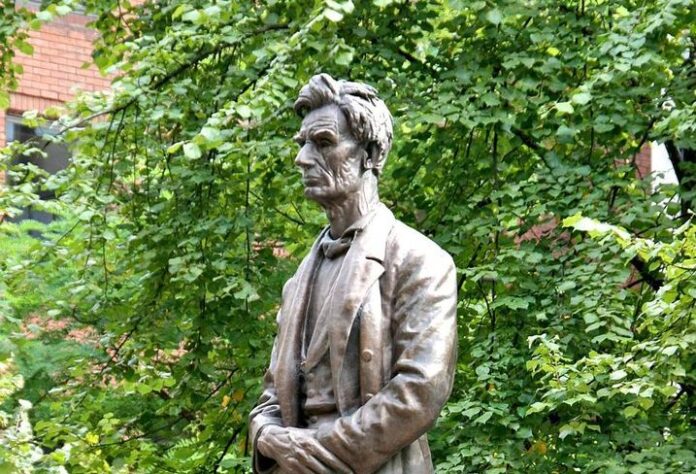

Abraham’s statue, sculpted from bronze by George Grey Barnard in 1914, was intended to stand outside the Houses of Parliament, a tribute from the United States marking 100 years of peace between the two countries since the British had set fire to the White House in a war which inspired the writing of the Star Spangled Banner.

The American sculptors depiction of what was described as a vigorous pose was far too controversial for London’s tastes, a more statesmanlike image would appear after the war, and the statue without a home came to Manchester which appealed to its civil war connections.

The statue arrived first in Platt Fields Park, (a copy still stands in Lytle Park, Cincinnati, Ohio) unveiled in 1919 and described as a symbol of the city’s unashamed liberal values despite the fact that the cotton industry was far from unanimous in its support for the Northern armies with workers in the Lancashire towns facing starvation and destitution with, it was estimated, over sixty per cent of the spindles not turning.

The Statue itself stayed until the 1980’s when it became the focal point, mounted on a new pedestal in Lincoln Square, its red granite plaque freshly scrubbed clean back in 2007 to celebrate the two hundredth anniversary of the abolition of slavery.