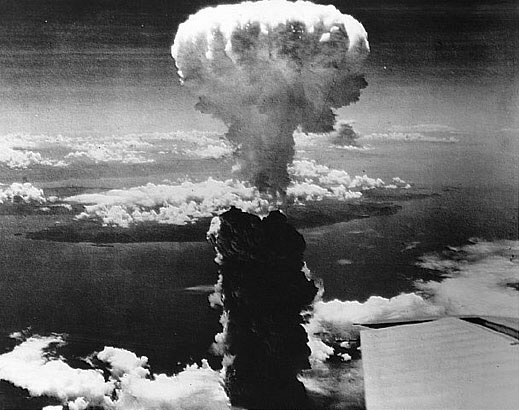

When President Truman announced in August 1945 that American forces had dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Manchester glowed as it celebrated its part in what was then considered a new triumph for the world.

The modern conception of what exactly an atom was, had been formulated in a laboratory at the University of Manchester by Ernest Rutherford, a native of Nelson, New Zealand. Considered a rather bluff man who looked like a farmer and never lost his provincial accent, who had arrived at Cambridge University in the 1890’s where he had begun initially to work on radio waves.

He would study the passage of electricity through gases and working alongside J. J. Thompson would be introduced to the nature of atoms, coming in contact with Dalton’s principles of sixty years earlier that gases, being a collection of free unbound atoms were unconstrained compared to solids and liquids.

In 1898 he would be elected as McDonald’s Professor of Physics at Montreal University but his period in Manchester from 1907 where he would be honoured with the Nobel Prize, not for physics but chemistry, would see him demonstrate through experiments that atoms had small positively charged nucleus surrounded by electrons, shooting atomic projectiles at the atoms.

The results were published in 1911 and would result in the period up to the First World War seeing the city recognised as a seat of scientific discovery on a scale not reached since the days of Dalton and Joule. After the war he would demonstrate the artificial disintegration of the atom, an experiment at the time not considered to have the theoretical importance of his earlier work but which would lay the foundations of the atom bomb.

He would return to Cambridge but his pupil, James Chadwick, educated at Moston Lane elementary school following his protégé to Cambridge was to discover the neutron in 1932, a particle that was found to have the power to penetrate the nucleus of atoms with ease owing to its lack of electric charge which in layman’s terms meant that it would not be repelled as it approached the core of the atom.

That same year another Manchester student, Professor J. D. Cockcroft was smashing atoms using machinery that had been developed at the Metropolitan-Vicker’s laboratories at Trafford Park.

President Truman was to refer to those experiments as being utilised in making the atom bomb, though the machine, whilst based on Cockcrofts prototype, was invented by a Californian professor.

There would be other connections to the secret work that took place in the American desert, Professor P. M. Blackett had been Langworthy Professor of Physics at Manchester University before the war and had discovered the positive electron and Sir Lawrence Bragg, also a Langworthy Professor of Physics back in 1919, who for many years lived in Lapwing Lane in Didsbury.

The press would hail these scientists, “the e’tommy bomb experts from Manchester” as we reveled in this atomic age. Atomic energy would give us an inexhaustible supply of energy for the future, superseding coal and oil, one correspondent explaining that there was enough energy in a pint of water to drive the QE2 across the Atlantic and back.

In 1947 the Manchester Museum was putting on an exhibition with a working demonstration of radioactivity and further research was being planned including two 11 tonne magnets under construction at Metropolitan-Vickers which would allow scientists to measure the energy provided from nuclear particles.

But the warnings were out there as well. Professor Blackett himself opening a travelling atomic energy exhibition at Victoria talked of the atomic bomb as a dangerous and tragic result of Rutherford’s experiments and speculating whether the benefits if this new energy would arrive before another war when they would surely be used.

The exhibition included blackened roof tiles from Hiroshima and a piece of molten congealed; still radioactive sand, from the deserts of New Mexico as well as a chart showing what would happen if a Hiroshima type bomb detonated over the centre of the city of Manchester which would have destroyed everything within a six mile radius, ruin all brick buildings within a 14 mile radius and kill immediately 200,000 people, half of Britain’s casualties during the Second World War.

Rutherford died two years before the start of the Second World War and would not see the destructive power which his experiments would indirectly lead to.

This piece is an edited version from a forthcoming book About Manchester to be released this autumn