An estimated 8.4 billion people could be at risk from malaria and dengue by the end of the century if emissions keep rising at current levels, according to a new study published in The Lancet Planetary Health.

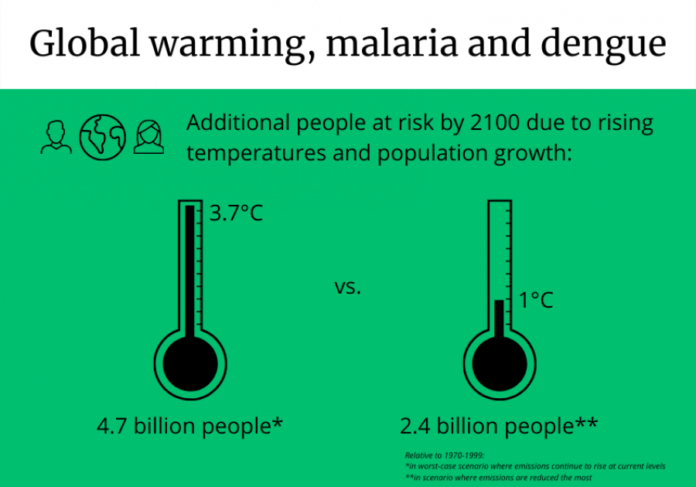

The research team estimates that this worst-case scenario would mean the population at risk of the diseases might increase by up to 4.7 additional billion people (relative to the period 1970-1999), particularly in lowlands and urban areas, if temperatures rise by about 3.7°C by 2100 compared to pre-industrial levels.

The study was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) with partners from Umeå University, Sweden; Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Italy; University of Heidelberg, Germany; and the University of Liverpool.

The team used a range of models to measure the potential impact of climate change on the length of the transmission season and population at risk of two important mosquito-borne diseases – malaria and dengue – by the end of the 21st century compared with 100 years earlier. They made their predictions based on different levels of greenhouse gas emissions, population density (to represent urbanisation) and altitude.

For malaria, the modelling for the worst-case scenario estimated a total of 8.4 billion people being at risk in 2078 (ie 89.3% of an estimated global population of 9.4 billion) compared with an average of 3.7 billion over the period 1970-1999 (ie 75.6% of an estimated global population of 4.9 billion). For dengue, the modelling estimated a total of 8.5 billion people at risk in 2080 compared with an average of 3.8 billion in 1970-1999.

Malaria suitability is estimated to gradually increase as a consequence of a warming climate in most tropical regions, especially highland areas in the African region (eg Ethiopia, Kenya and South Africa), the Eastern Mediterranean region (eg Somalia, Saudi Arabia and Yemen), and the Americas (eg Peru, Mexico and Venezuela). Dengue suitability is predicted to increase mostly in lowland areas in the Western Pacific region (eg Guam, Vanuatu, Palau) and the Eastern Mediterranean region (eg Somalia and Djibouti), and in highland areas in the Americas (eg Guatemala, Venezuela and Costa Rica).

The research predicts there will be a northward shift of the malaria-epidemic belt in North America, central northern Europe, and northern Asia, and a northward shift of the dengue-epidemic belt over central northern Europe and northern USA because of increases in suitability.

All the scenarios predicted an overall increase in the population at risk of malaria and dengue over the century. However, the impact would reduce substantially if action were taken to reduce global emissions, according to the modelling.

In the scenario where emissions are reduced the most – greenhouse gas emissions decline by 2020 and go to zero by 2100 and global mean temperature increases by 1°C between 2081 and 2100 – an additional 2.35 billion people are predicted to be living in areas suitable for malaria transmission. For dengue in this scenario, the modelling suggests 2.41 additional billion people could be at risk.

The study highlighted that if emission levels continue to rise at current levels, tropical high-elevation areas (more than 1,000 metres above sea level) in areas such as Ethiopia, Angola, South Africa, and Madagascar could experience up to 1.6 additional climatically suitable months for malaria transmission in 2070-2099 compared with the period 1970–1999.

The study predicted that the length of the dengue transmission season could increase by up to four additional months in tropical lowland areas in south east Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Indian sub-continent.

First author Dr Felipe J Colón-González, Assistant Professor at LSHTM, said: “Our results highlight why we must act to reduce emissions to limit climate change.

“This work strongly suggests that reducing greenhouse gas emissions could prevent millions of people from contracting malaria and dengue. The results show low-emission scenarios significantly reduce length of transmission, as well as the number of people at risk. Action to limit global temperature increases well below 2°C must continue.