In the first of our articles celebrating all that is great about the region-we look at Manchester’s wonder material Graphene

This month sees the fifth anniversary of the opening of the National Graphene Institute (NGI).

Since it opened its doors the NGI has played host to some of the world’s most famous faces and set the ball rolling in the advancement of graphene and other two-dimensional materials.

Behind it sits Graphene, a wonder material incubated at Manchester University promising mobile phones worn as floppy as wristwatches, bendable and unbreakable computer screens, glasses that double as computers, the early detection of genetic diseases and a green transport revolution led by hydrogen powered cars.

The scientist behind it, Andre Geim, was born in the Black Sea resort of Sochi in the Soviet

Union in 1958. Referred to by many as a maverick, he was the first scientist to win both a Nobel and an Ig noble prize for physics, a former lieutenant in the Soviet Army, he studied the technology of intercontinental missiles. Known for amusing his students by drinking liquid nitrogen during lectures, his other inventions including a sticky tape that allows the wearer who puts it on the sole of his shoe to walk up walls.

He was lucky that his career was developing at the time the Soviet Union was opening up to the west and in 1990 he was awarded a place at the University of Nottingham, his wife describing him as being like a child in a sweet shop when he saw the opportunities available in a freer society.

He became an assistant professor at a Dutch university where he would carry out one of his more eccentric experiments for which he was awarded his Ig noble prize, messing around in one of his famous Friday night experiments with a powerful magnet and producing a levitating frog.His experiments were shunned by many learned colleagues as being the science of the 19th century and simply carried out to amaze children.

Manchester though would welcome him with open arms, arriving in 2001 as a professor of

physics where he created a lab where students were able to experiment without constraint in the same way that he made the frog fly.

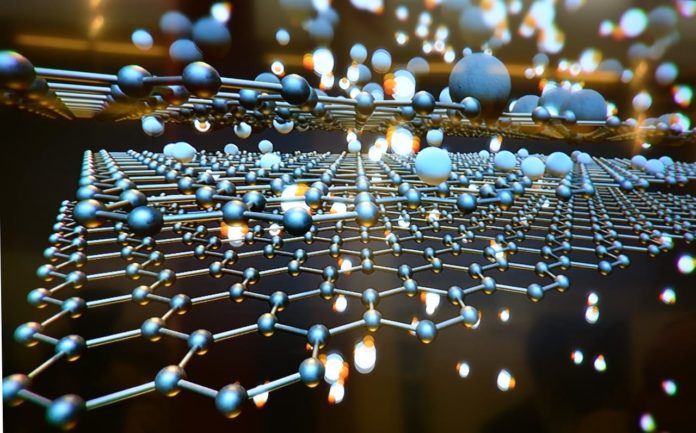

But this technical madlab would see the discovery a new substance, just one atom thick

stronger than diamond but stretching like rubber and able to conduct electrons a million times better than copper, the result of an experiment where graphite from a pencil was stripped away layer by layer using sticky tape.

Its uses have multiplied since the first foundation stone on the Institute was laid.A graphene lightbulb with lower energy emissions, longer lifetime and lower manufacturing costs.

A graphene oxide membrane which was able to filter out common salts. Known as a ‘graphene sieve’ this demonstrated real-world potential of providing clean drinking water for millions of people who struggle to access adequate clean water sources. The team have gone on to turn whisky clear and produce membranes for oil separation.

The first graphene running shoes were launched. Collaborating with inov-8, the brand has been able to develop a graphene-enhanced rubber. Rubber outsoles were developed that in testing outlasted 1,000 miles and were scientifically proven to be 50% harder wearing.

But has Manchester and the UK truly made the most of this discovery? George Osbourne the then Chancellor back in 2011 Chancellor of the Exchequer came running to Manchester to announce that “Tomorrow’s World is being shaped in the city” when he announced that the Graphene Institute would be built back in 2011.

Could Manchester overcome what is commonly known as “the European Paradox” which sees the continent able to produce cutting-edge scientific research, but not being so good at turning it into marketable products.

Even its inventor recognises the problems, telling the Financial Times that western civilisation has no big institute that cares for such projects. “Maybe this is why the centre of wealth goes so far east, where advanced institutes of technology, such as Samsung, still support industrial development ”and adding that he spends twenty-per cent of his time trying to collaborate with other companies but often struggles to secure funding as companies are reluctant because of competitive pressures to see beyond three to five years.