Two hundred years ago this month, rooms for the study of Anatomy opened in Manchester at No 69 Bridge Street.

Four students enrolled that week and very quickly the institution would be causing controversy, especially over its procurement methods of its bodies, its founder would find himself up in front of the magistrates.

Yet it quickly expanded and it would place Manchester and its founder at the heart of anatomical research in nineteenth century Britain.

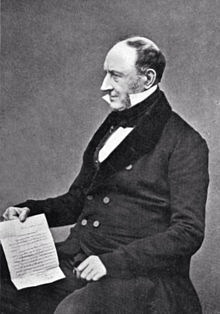

Joseph Jordon was born at Water Street, in March 1787, the youngest of six children his family’s origins were Dutch, his grandfather settling in Manchester in 1745 in company with his cousin Blacklock, a founder of the firm of Bradshaw, Blacklock & Co, publishers of the railway time-tables.

His father William was ‘a blue printer on calico’, a pioneer of the art in his neighbourhood, his mother Mary came from Gorton.

He attended school at the Rev J Birchall’s, his interest in anatomy instilled at an early age where. “His investigation into the anatomy of the school clock”, says his biographer, Dr F W Jordan, “led to the sudden termination of his studies under Mr Birchall.”

After leaving the tutoring of Mr Birchall, he became apprentice to Mr John Bill, surgeon to the Manchester Infirmary where his work consisted chiefly of pill-making in a cold cellar, until his mother removed him when he then joined Mr William Simmons, who was on the honorary staff of the infirmary, spending the major part of his time in the infirmary, where he dissected and engaged in pathological research, before completing his professional education by attending lecture courses in Edinburgh.

He joined the army in 1806 with his country fighting Napoleon, as a ensign becoming Assistant Surgeon to the Royal Lancashire regiment a year later but never saw action, becoming bored with army life and resigning five years later to continue his studies and returning to Manchester in 1812.

His return to Manchester saw him embark on a career in medical education which saw the founding of the School of Anatomy two years later.

Many stories have been told in Bridge Street”, wrote his biographer sDr Jordan,

“of hairbreadth escapes with bodies; on one occasion the body of a man was completely dressed and set up in a gig between two persons and driven homewards….” The ghastly cargo was smuggled through a turnpike with great difficulty. “Once Mr Jordan was fined twenty pounds by the magistrates, reluctantly as they admitted, and his resurrectionist was condemned to undergo twelve months’ imprisonment and to pay a fine for rifling a grave. I use the term reluctantly advisedly, because the magistrates admitted that a medical student was compelled to dissect in order to obtain his qualification to practise, and the law stated that bodies should not be used for the purpose of dissection. It was not, however, his first offence, for he had got into trouble as a body-snatcher so long ago as the days of his military service, when he was pounced upon by an outraged father and mother for being in possession of the corpse of their child. He had on that occasion to beat a precipitate retreat from Kidderminster, where he was quartered.”

Later he would admit his part in body snatching in a speech in 1854, telling the audience that ” the students of my time were obliged to steal bodies and I am not ashamed to say that I was one of the parties”

Three years later, such was the success of the school, they moved to larger premises In 1817, at 4 Bridge Street. The original school became his house, and stayed in use well into the 1870’s.

These premises comprised two lofty rooms, one of which was used for dissections, the other as an anatomical museum containing some fine preparations. This museum was regarded by the local domestics as being haunted.

He continued to court controversy. In 1819 with much opposition, while concerned for the plight of single pregnant women in the town, he established the Manchester and Salford Lock Hospital for unfortunate women, along with Dr Locke, an expert in Caesarian operations.

Two years later his course was finally recognised by the Royal College of surgeons, the first in a provincial town and in 1823 he built a medical school in Mount Street where he would lecture for many years.

In 1835 after many attempts he was finally appointed to the honorary staff of the Manchester Infirmary and it seemed that society had finally accepted his anatomical practices.

He would in later life become a founding member of the Chetham’s Society, served as vice-president of the Manchester Royal Institution and consulting surgeon-extraordinary to the Salford Royal Hospital.

He continued to live in Bridge Street, a bachelor until 1871, when ill health forced him first to move to West High Street, Salford, then to Stroud, and finally to Hampstead, where he died in March 1873.

Upon the announcement of his death the Manchester Guardian wrote that it was ” by no means going too far to say that his establishment of provincial medical schools was one of the most important of all reforms to have taken place in medical education” adding that

” to the last he was a thoroughly large minded and large hearted medical man who was never prejudiced against a project because it was new or bigoted in its favour because it was old.”