The little-known history of Warth Mills WWII internment camp in Bury, is set to be revealed with the launch of a commemorative events programme and website.

The Warth Mills Project will tell the story of Warth Mills and its internees, which included Italians who had resided in Britain for decades and German Jews who had fled Nazi death camps. Many significant artists were locked away there, including Kurt Schwitters and Paul Hamann. General internment only began to end following the sinking of the SS Arandora Star on July 2, 1940, when hundreds of men who were being taken from Bury to Canada drowned after the ship was torpedoed.

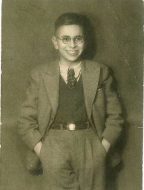

Henry Wuga, 94, was interned at Warth Mills in 1940 and is the last known survivor. He said: “I was born into a Jewish German family in 1924 and our family business was in the catering industry. When I was 14 in 1938, my mother took me out of school as she thought it was wise that I learned a trade. I went to Baden Baden in the Black Forest and worked as an apprentice Commis Chef for six months at a strictly kosher business, before returning home in November 1938.

“When war broke out in early 1939, my parents were understandably concerned for my safety and found me a place on Kindertransport for evacuation. Kindertransport was a rescue effort organised by The Central British Fund for German Jewry (now World Jewish Relief) which it had set up after going to our government and asking if there was any way that Jewish children could be saved from Nazi persecution through evacuation. The Home Secretary of the time, Samuel Hoare, was from a liberal Quaker background and agreed, saying if the necessary funds could be raised quickly, it could be pushed forward. The plan was passed in government within three weeks, a lot quicker than things go through nowadays.

“I got my place on Kindertransport at the age of 15. This involved travelling on a train from Nuremburg and there were around 100 children being evacuated. I didn’t have any siblings so I went on my own and didn’t know anyone but, having worked away for six months at 14, I felt like I could handle it. However, some of the other children on board were only six or seven years old at the time and had never been away from parents before so it was an awful journey – full of crying children who were being taken away to safety, but also away from their parents. They didn’t understand what was happening. I can remember when we reached Holland, there were ladies there to meet us with hot chocolate.

“We passed through Holland and got on a boat to Essex before reaching Liverpool Street Station in London by train. Some children were collected by people who had acted as guarantors for us and I remember it being like a cattle market, with siblings separated. The children without a guarantor were taken to a holiday camp.

“I travelled from Euston to Glasgow Central with two boys and one girl on the Royal Scot. This was a train with waiter service and I’d never seen anything like it! On arrival at Glasgow, I was collected by my guarantor, a nice Jewish lady called Etta Hurwich who was in her late 60s to early 70s. She was Latvian and had agreed to take me in. I had a comfortable home there, Etta was extremely kind to me and I was sent to school locally. I wrote to my parents, but I had to send my letters home via my uncle in Brussels.

“In 1940, the police unexpectedly came to our house in Glasgow and I was arrested and taken into custody, being sent to the High Court in Edinburgh and charged with the crime of corresponding with the enemy – which was a very serious offence. This was because of the letters I had sent to my parents via my uncle. I was charged and declared a Dangerous Enemy Alien: Category A, taken back home and given one hour to pack and one phone call. This all happened very quickly. I was only 16 years old, which was under the age of internment.

“Nevertheless, I was sent straight to an internment camp, Mary Hill Barracks in Glasgow, which was a large military establishment. I was held as a prisoner with 25 German seaman and, as a 16-year old Jewish boy, it wasn’t a pleasant experience. I was called a ‘dirty Jew’ among other things.

“I was then taken to another internment camp, Donaldson School in Edinburgh. While I was there, those in charge asked if there was anyone who could cook. Because I had spent time as an apprentice chef, I found myself suddenly in charge of the kitchen – with 25 German sailors as my staff, can you imagine!

“I was moved to another internment camp at York Racecourse. I can recall one of the Sergeants coming into the kitchen to get his own provisions for the train and I had to tell him there was nothing left. I spent a week at York before being taken to Warth Mills in Bury near Manchester.

“While all the other internment camps were rough, internees were treated reasonably, but Warth Mills was a completely different story. It was awful and I remember I was still only 16 years old. I was strip searched and had any valuables taken away. I was given a hessian bag and sent to a place where hundreds of men were already – it was a crazy, horrible place. Extremely dangerous and primitive, there was overhead steel hanging down and little food. We all slept on straw. I can remember we had to cross an open yard to get around and, on one occasion, a guard ordered everyone to stop or he’d shoot us – and one man begged to be shot. That was an indication of what it was like.

“One thing I remember about Warth was, while there was little food, there was bizarrely a good supply of Carnation Milk. I’ve never been able to touch it since.

“One thing I remember about Warth was, while there was little food, there was bizarrely a good supply of Carnation Milk. I’ve never been able to touch it since.

“I can also remember one day, one of the overhead transmission beams fell down and killed someone – I think he was a Catholic Priest. There was one water tap for 60 men and it was extremely dangerous…there were casualties in Warth Mills, obviously.

“I was at Warth for seven to ten days and then moved to Huyton in Liverpool for two nights before being transferred via boat to the Isle of Man where I stayed for around ten months. My roommate was a German officer and as it turned out he was an MI5 spy – so it was suspected that my letters were being used for illegal purposes.

“It was from the Isle of Man that I was eventually released. Here I was – a young kid among professors and people who eventually won the Nobel Peace Prize. It was like being at a university in an intellectual and academic environment and I could hear lectures on any subject.

“All the letters I sent to my parents and Uncle which led to me being charged with corresponding with the enemy are now archived at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. I never saw my father again after being evacuated as a 15-year old as he died of a heart attack. But my mother survived the War after being hidden by Catholic friends. I did manage to see her again when she got permission to come here to live with us in 1947.”

Henry returned to Glasgow on release in 1941, working again in the restaurant and hotel trade and meeting Ingrid Wolff, his future wife, when he was 20. Ingrid had also been a Kindertransportee. Henry became a chef and he and Ingrid married and started a kosher function catering business in 1960.

Henry and Ingrid have now been married for 73 years and have two daughters and four grandsons.

He continued: “Ingrid and I are now enjoying our retirement in Glasgow. Since stopping work, we aimed to give back to our local community and I did voluntary work with Jewish Care and the Prince and Princess of Wales Hospital. I was also honoured to receive the MBE in 1999 from Her Majesty the Queen for Services to Sport for Disabled People, which recognised my long association as a Ski Bob instructor for the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association.

“Throughout the time of my internment, I was underage as I was not 18. While in internment, we were allowed one letter a week. I had no-one to write to, so my letters were addressed to Eleanor Rathbone, an MP for the Universities. She was very liberal and helped the internees to voice unjust internment via the Manchester Guardian where we asked to be released and help the War Effort. These letters were eventually read out in the House of Commons and, about ten years ago, I managed to get hold of all of my documents. I am now documenting my experience in detail so that it is not forgotten.”

Warth Mills was originally built in 1891 by Mellor Limited. It is situated in the Redvales area of Bury, alongside the River Irwell. In 1911, Warth Mills housed 46,000 spindles and 600 looms and employed people from the local area. After years of disuse, it became an internment camp in 1940. As Northern Europe fell under Nazi control, Churchill instructed authorities to intern all Italians, Germans and Austrians resident in Britain. These “enemy aliens” included Italian chefs and café owners, Jewish artists and academics who were fleeing persecution – most of them posed no threat to British security and some went on to fight with the allied forces.

The building still exists and is now owned by St Modwen Properties Ltd and used as office space and industrial units.

The Warth Mills Project is led by Unity House, based at The Met in Bury, and successfully bid for £64,500 from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF). The project started in 2017 when volunteer researchers began creating a digital archive and partners include St Modwen, The Met, Manchester Jewish Museum, Bury Art Museum, Bury College, Archives+, International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Bury Council, Imperial War Museum, Manchester Art Gallery, Mill Gate Shopping Centre, Refugee Week, The Fusilier Museum, World Jewish Relief, Bury College, Workers’ Educational Association and University of the Third Age.

Richard Shaw from Unity House said: “The internment of Italians and German Jewish refugees has never really been explored and few people know about the full history of Warth Mills. We are delighted to finally honour the internees by telling the stories of the hundreds of men who never made it home to their families.”

The Warth Mills Summer 2018 events programme includes an art showcase by students at Bury College, music recitals and events honouring internees.

Find out more about the Warth Mills Project, follow on Twitter @WarthMills or Facebook @TheWarthMillsProject