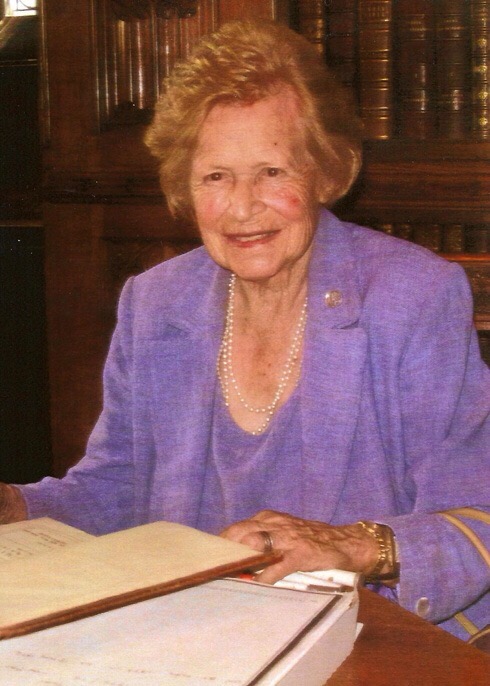

Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw who died last year at the age of one hundred and one overcame profound deafness to carve a career in mathematics, politics and education.

Lord Mayor of Manchester, one of the prime movers behind the creation of the Royal Northern College of Music and one of the first to solve the problem of the Rubik cube, she published a number of eminent papers on mathematics and advised Mrs Thatcher on education policy.

She was born into the Timpson family in Manchester in 1912, daughter to Mary and Charles, her father was a local magistrate.

An early childhood illness saw her lose her hearing and she was to be in her thirties before she acquired a hearing aid, but her disability did not prevent her education being taught to lip read in a pioneering treatment at the University of Manchester.

She was educated at Lady Barns House school and St Leonard’s boarding school, St Andrew showing an early aptitude for mathematics, a discipline she felt which had no need for her ears, winning an open scholarship in mathematics to Somerville College, Oxford, where she also excelled at hockey.

In 1937 she joined the Shirley Institute, the research centre into the cotton industry based in Didsbury as a statistician, marrying Robert Ollerenshaw two years later, a boy she had known since her school days.He would serve as a military doctor during the war and would later work in the radiology department at Manchester’s Royal Infirmary.

Having a career break to bring up a son and a daughter, she returned to part time teaching at the University of Manchester and was elected to Manchester council as a Conservative councillor for Rusholme in 1956, a position she held for twenty six years, having previously served on the local education board.

“To serve on the Manchester education committee seemed an ideal way of giving the public service that I had been brought up to believe should be a main objective for those not obliged to earn their own living,” she later wrote.

Her long political career took her to the city council and numerous national education committees, including stints in Margaret Thatcher’s administration in the 1980s.

But it is in It was in mathematics that she may be most remembered. 1964 the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications was founded and Kathleen was a foundation fellow and, in the late 1970s, served as vice-president, then president of the institute, 1978-79.

In her presidential address she spoke of “the magic of mathematics” and gave an elegant and enthusiastic survey of some splendid mathematical proofs, using examples as diverse as the angle of screws in the Manchester sewage works and the structure of honeycombs and wasps’ nests.

Her book Most-Perfect Pandiagonal Magic Squares, was published in 1998 with David Brée, a computer scientist who rented one of her rooms for several years.Magic squares are arrays of numbers in which the sums along the rows, columns and diagonals are all equal. From that work she was able to publish one of the first solutions to the Rubik’s cube.

She damaged the tendons in her left thumb so badly with repeated turning of the cube that she required surgery.

She was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1971 for her services to education, was awarded honorary doctorates by five leading universities, was a companion of the Royal Northern College of Music and was chair of its governing body for the first 15 years.

After her husband died in 1986, she took up astronomy, purchasing a telescope and creating an observatory at her home. She learned everything she could about astronomy and carefully arranged to observe eclipses and comets, either on trips or from her cottage. During the next few years she upgraded her telescopes several times, eventually donating one to Lancaster University.