Most people who come into Manchester City Centre will know John Dalton Street,and those that walked into the entrance of the Town Hall before its closure may have noticed the statue to him but how many know who is and how he contributed to the region?

John Dalton was born in 1766 in the village of Eaglesfield in Cumberland the son of a smallholding farmer and weaver. The family were Quakers, a religion that at the time,excluded him from traditional routes into social and professional society and precluding him from a university education.

The young Dalton was lucky however his enquiring mind and appetite for study would come to the attention of local landowner Elihu Robinson, sharing his particular interest in meteorology.

By the age of twelve the young boy was teaching the local children in a barn in his village and at fifteen would move to Kendal where he would meet another well connected Quaker; the Blind Scholar John Gough who encouraged his study of meteorology, when he started a daily weather record which he would continue for the rest of his life.

Dalton would advertise as a tutor in astronomy and mechanics but his religious background prevented further advancement.

Manchester would offer him the chance to expand his knowledge in the form of the Unitarians who, like the Quakers found social advancement blocked by their dissenting beliefs. Thomas Percival had set up the Manchester Academy in the 1780’s with the express purpose of educating those excluded by means of their beliefs and Dalton would move there in 1793.

After six years teaching Dalton resigned his post to concentrate wholly on scientific investigation with his interest in chemical research beginning in 1796, devoting his life from that point onwards to the study of the laws expressing the chemical and physical properties of gases.

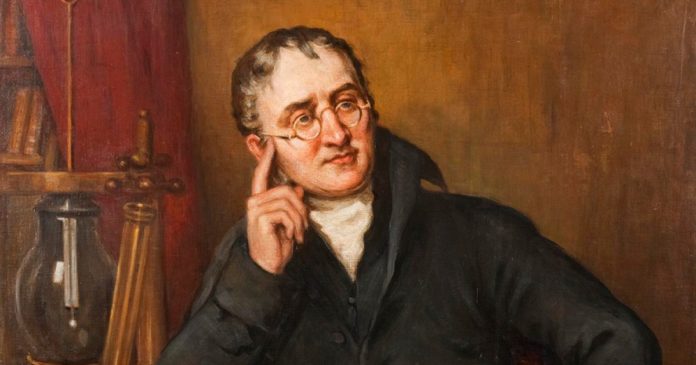

His research though began with colour. He was colour blind and would ceasingly experiment upon himself, wearing his bright crimson doctorate gowns that to him looked drab. His announcement on Atomic theory would win him fame across Europe and besides being elected a fellow of the Royal Society, he would be granted the rare honour of being a corresponding member of the French Academy of Sciences. Yet he remained a quiet and reserved man.

A story is told of a French student who journeyed to Manchester to pay homage to his hero in a small room in a back street house teaching a young boy to add using chalk and slate. When later he would be presented to King William the Fourth, who asked “Well Mr Dalton, how are you getting on in Manchester” he replied in his strong Cumbrian vowels, “mebbie sae but what can yan say to siclike fowk”.

His dress, wrote a lifelong friend, “was that usually worn by the Quakers, avoiding however the extreme of formality and always of the finest texture”. He worked daily in a laboratory put at his disposal at the premises of the Literary and philosophical society on George Street and he would remain living in the same house for over thirty years.

As one writer put it, he was Heine’s Immanuel Kant, “rising, coffee drinking, writing, collegiate lectures, dining, walking, each with its own set time. His pleasure was a Thursday afternoon, game of bowls which he played at the Dog and Partridge near to Stretford, when afterwards he would go home “ to consume the food needed to supply the metabolism of the body and to sleep in order to obtain the brain power needed for the next day’s work.

That brain power would, with the help of Newton one hundred years earlier, overturn a two thousand year Democritean theory that matter consisted of invisible particles moving constantly in an empty space and Aristotle’s four elements of fire, water, earth and air.

Dalton’s atomic theory was based on his interest in meteorology; the nature of water vapour and clouds and water, he observed, could sometimes disperse itself into a lighter air. If these substances were different, why didn’t they separate out into different layers?

Dalton would propose that all the atoms of each element weighed the same, that the particular weight could vary for separate elements and that atoms of these elements combined with each other in simple fixed proportions to make larger atoms which would become known as molecules.

He would remain in Manchester until his death in 1844, when by now internationally famous he would lie in state at the old Town Hall on King Street, the epitome of a humble man who had reached the heights of scientific magnitude and forty thousand citizens would file past in homage to the man of humble beginnings who had put the city firmly on the scientific map.