For most of this year, people all over the world have been anxiously awaiting a viable COVID-19 vaccine that could finally bring the ongoing pandemic to heel. And earlier this month, they finally got what they were waiting for: the first approved vaccine is now available in Manchester and elsewhere.

But for anyone old enough to remember earlier pandemics, the vaccine seems too good to be true. And that makes sense. According to the government’s chief scientific advisor Sir Patrick Vallance, a vaccine of this type has never taken less than five years to develop. But this time around, the boffins had a revolutionary new tool at their disposal.

It’s called messenger RNA (mRNA), and it represents a radically different approach to vaccine development. But contrary to popular belief, it didn’t develop overnight. Instead, it’s the culmination of over 30 years of continuous research by scientists around the world. It just so happened to be ready right when we needed it most.

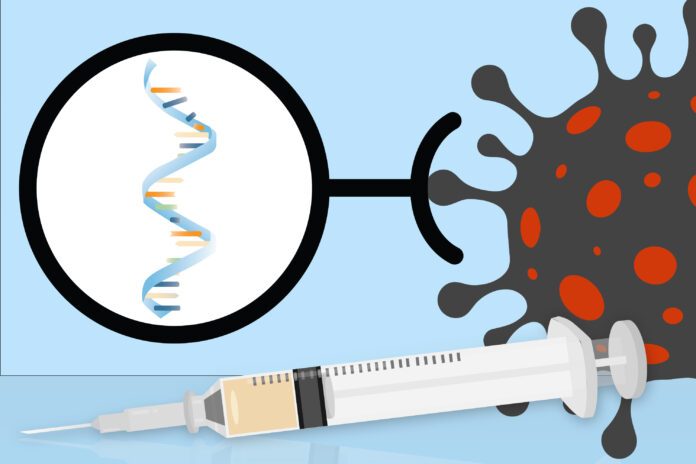

In short, mRNA is a genetic material that acts as a sort of blueprint to instruct our bodies to produce different types of proteins. And in this case, it’s being used to tell our bodies to manufacture the protein spikes – the red bits you see on representations of the coronavirus – to provoke an immune response that gives us immunity to the full-blown virus.

In older vaccines, it was necessary to culture large amounts of a target virus, which is both time-consuming and labour intensive. Those cultured samples would then be weakened to become the basis for a vaccine that would trigger an appropriate immune response. But mRNA, by comparison, can be mass-produced in labs with little trouble. And because it’s based on genetic information about a target virus, finding the right instruction set is a far simpler affair that doesn’t require handling of any infectious agents.

And it’s important to note that the technique to synthesize custom mRNA outside of the body built on several previous discoveries and technologies without which none of this would be possible. First and foremost is our current understanding of how human DNA functions and the role mRNA plays in protein synthesis. There’s also specialized equipment like multi-mode microplate reader variants by BMG Labtech and others as well as reagents and other DNA sequencing gear.

All of those things made it possible to develop coronavirus vaccine candidates in less than a year. In the case of the Moderna vaccine, developing a candidate took a scant 42 days from when scientists in Wuhan, China released COVID-19’s genetic code to scientists around the world. And we’re likely seeing is only the beginnings of how mRNA technology might transform medicine.

There are already other vaccines in development using mRNA that might put an end to some of the world’s most dangerous and difficult to treat diseases. That means we could soon see an end to Ebola, Zika, and Influenza to name a few. But it isn’t just viruses that could be eradicated. Scientists are also working to harness mRNA to cure melanoma and other types of cancer, as well as diseases like cystic fibrosis.

In a way, the COVID-19 pandemic may have acted as an accelerant of the work on biotechnology that could be the most important medical breakthrough since the invention of penicillin. And although the price paid in lives and suffering has been steep, we can at least be thankful that it’s yielding a breakthrough that might prevent similar pandemics from ever wreaking havoc on the world again.

So, as we head into 2021, we’ll be stepping into a world forever altered by the COVID-19 pandemic. But we’ll also be stepping into a world of medical possibilities that would have seemed unimaginable only a few short months ago. And that may be the most fitting – and redeeming – coda to a 2020 that has seemed at once interminable and unbearable.