A new book out in Manchester aim to shed light on the life of teenage boys.

Being Boys: Youth, Leisure and Identity in the Inter-War years by Professor Melanie Tebbutt at Manchester Metropolitan University has just been published in paperback.

In it she says that young people in the 1930s were the first generation to experience a kind of mass teenage culture, with boys learning to smoke by watching their Hollywood idols on the newly-affordable cinema screen, or beginning to idolise sportsmen by collecting cigarette cards of cricketers or footballers.

Prof Tebbutt said: “We tend to think of such young men in a very narrow way because we’re often fearful of them. I wanted to write a book which presented a broader view, one which explored the difficulties that some had expressing their feelings, and the confidence and expertise they built up through their leisure enthusiasms. I wanted to show them as having agency in their lives, rather than as individuals who had things done to them.”

The book’s theme is the leisure pastimes of working-class boys and young men in the interwar years, from cinema, dancing, walking and cycling, to hobbies and youth groups like the Boys’ Brigade.

Prof Tebbutt said: “This generation of boys in their teens did not have the shadow of the First World War hanging over them, unlike their counterparts in the 1920s. The decade in which they grew up was on the cusp of cultural changes which became much more visible with the emergence of mass teenage culture in the 1950s.

“Popular commercial culture in the 1930 was becoming more visual. The cinema was the most popular leisure activity among the young, offering models of glamorous adult behaviour, from how to look sophisticated when holding a cigarette to ‘edgy’ gangster fashion styles.

“A celebrity culture of film stars and sporting heroes was emerging and personal advice columns were becoming popular in mass-circulation newspapers and magazines and attracting letters from correspondents who included young men as well as young women.”

Being Boys explores the impact of these new trends on individuals through diaries, autobiographical accounts and letters to advice columns. Unlike the aggressive behaviour with which they are often associated, the book reveals some of the hesitancies and anxieties of growing up male in the 1930s.

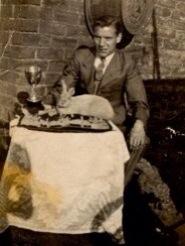

Prof Tebbutt was inspired to start researching the subject by her own father’s diaries, which he left behind when he passed away.

She said: “Historians are like magpies and I always had an interest in the diaries he said he had. Not a lot of material is deposited in archives from working class people, so it was a rare opportunity.”

The diaries chronicle the sort of leisure activities that young men would get up to after work at a time when all sorts of new cultures were emerging.

Prof Tebbutt says that boys gained confidence they got from being involved in certain activities, such as breeding and showing rabbits, and from the fact that they acquired a certain expertise through the passions they had.

Rather than seeing all working class boys as “delinquents”, as they are often portrayed, Prof Tebbutt said she wanted to research their “quieter enthusiasms”.

“I was trying to get under the skin of ordinary boys and their daily lives, and some of the everyday difficulties – it was much harder to talk about themselves compared to girls.”