On August 13, 1964, the last two executions on British soil took place.

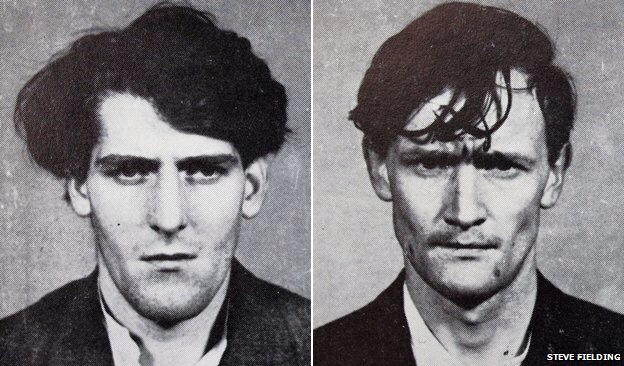

The hangings occurred simultaneously in Manchester at Strangeway’s prison and Liverpool, putting to death 21-year-old Peter Allen and 24-year-old Gwynne Evans, both sentenced for the murder of John West, a Cumbrian laundry driver.

John West, who lived alone, had returned to his home on 6 April 1964. At about 3:00 am the following morning his next-door neighbour was awoken by a noise in West’s house and, looking out of the window, observed a car disappearing down the street.

The neighbour called the police, who found West dead from severe head injuries and a stab wound to the chest. In his house the police found a raincoat in the pockets of which was a medallion and Army Memo Form. The medallion was inscribed “G.O. Evans, July, 1961”, and the memo form had the name “Norma O’Brien” on it, together with a Liverpool address.

Norma O’Brien was a 17-year-old Liverpool factory worker who told the police that in 1963, while staying with her sister and brother-in-law in Preston, she had met a man called “Ginger” Owen Evans. She also confirmed that she had seen Evans wearing the medallion.

Forty-eight hours after West’s murder, Gwynne Owen Evans aged 24, and Peter Anthony Allen aged 21, were arrested and charged with the crime. Evans lodged with Allen and his wife in Preston, and was found to have a watch inscribed to West in his pocket. Both had criminal records.

Although Evans blamed Allen for beating West, he admitted to stealing the watch, and under further questioning it became clear that he had masterminded the whole incident. In his turn, Allen stated that they had stolen a car in Preston and driven over to West’s house so that Evans could “borrow” some money from his one-time workmate.

Allen and Evans were tried together at Manchester Crown Court in July 1964 charged with capital murder under the Homicide Act 1957, because West had been killed in the course of a theft. During the trial the judge asked the jury to decide if the murder had actually been committed by one of the two men alone; in the latter case the other would only be found guilty of non-capital murder at the most. The jury found both men equally guilty, and both were sentenced to death by hanging.

The executions merited little media coverage at the time but they would be the last as a debate over capital punishment that had been simmering since the 1920’s reached fruition.

Everyone had thought that Clement Atlee’s Labour government of 1945 would carry out abolition but they argued that the death penalty was an effective deterrent, that public opinion opposed abolition and that the ‘unsettled post-war environment’ made it an unsuitable time for experimentation.

In 1957 the law on capital crimes would change after three high profile cases. Derek Bentley, hanged for the murder of a policeman at the age of 19, even though he did not fire the fatal shot and had a mental age of 11.

Timothy Evans, executed for the murder of his wife Beryl and baby daughter Geraldine, when the perpetrator was serial killer John Christie, who lived in the basement flat of their building and Ruth Ellis would become the last woman to be hanged in Britain.

The 28-year-old was executed in 1955 for the shooting of her lover David Blakely. After 14 minutes of deliberation the jury condemned her to death in spite of a huge outcry, protests and petitions.

The 1957 Homicide Act represented an uncomfortable compromise, introducing the new concepts of capital and non-capital murder with only five types of murder still demanding the death penalty.

A month after the executions in Manchester and Liverpool the prime minister, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, was told by the home secretary, Henry Brooke, that ‘the Homicide Act is unworkable in its present form and the next Home Secretary, of whatever party, will have to end the death penalty’.

The following month Harold Wilson formed a Labour government, the first to support abolition and a private members bill with a free vote was passed the following November.

It wasn’t quite the end of capital punishment though.The Bill carried an amendment under which the Act would expire in July 1970 unless both Houses voted again for abolition and the following year would see two high profile cases, one In Manchester when the crimes of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley came to light.

In the face of a storm of political protest, the debate on abolition took place with a free vote in December 1969 and after three days of debate, both Houses voted in favour of abolition.