As Parliament prepares to debate the controversial proposal that would give legal backing to so-called ‘three-parent babies’, a Manchester academic says the proposed change in the law is almost certainly a good thing.

The last few days have seen much debate over the issue in the media and the wider world over the process that allows the use of mitochondrial transfer technologies, whereby defective mitochondrial DNA in a human egg can be replaced with healthy DNA from a female donor.

Currently around one hundred and fifty children every year in the UK suffering from mitochondrial disease, or mitochondrial failure.

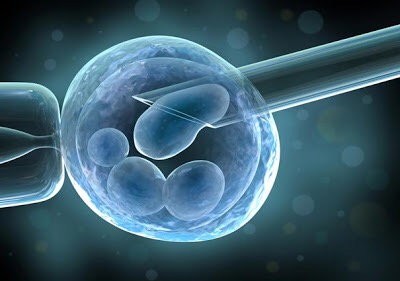

Children already born with the disease cannot be treated but the process to be debated replaces the whole workshop of the cell at the very earliest stage of human development by taking an egg from a healthy woman and remove its entire nuclear DNA leaving all the organelles of that cell, including healthy mitochondria.

Then the nuclear DNA, which contains all the instructions for life, is transferred from the sick woman’s egg to the healthy egg.

The resulting child will be genetically the child of the nuclear donor, except without mitochondrial disease argue its proponents.

Dr Iain Brassington, senior lecturer in bioethics at The University of Manchester, says ahead of the vote tomorrow

Dr Brassington said: “Parliament will have to decide this week whether to give legal backing to the use of mitochondrial transfer technologies, which offer a way to prevent a range of inherited illnesses with high morbidity and mortality. The proposed change in the law is almost certainly a good thing.

“There are significant moral concerns that rightly colour the debate about the use and legalisation of such technology. Foremost among them is a concern about safety: ought the law to be allowing a procedure the outcomes of which, over the course of a lifetime, are uncertain? It is true that there is a risk of harm to the future child – and, because of the nature of the technology, to an indefinite number of future generations? However, the same concerns apply to any new medical technique; if they are not enough to end all medical innovation whatsoever, it is hard to see why they should be enough here.

Opponents of the process, including the Church of England, argue that Introducing laws to allow three parent babies would be ‘irresponsible’ saying that there has not been sufficient scientific study or informed consultation into the ethics, safety and efficacy of mitochondria transfer.

If the new legislation is passed in the Commons today, it will be laid before the House of Lords on February 23rd and if successful, the first human trials could take place from October and the first babies born by Autumn 2016.

Professor Brassington says

the relevant question to ask is not whether the procedure is risky. We can take it as read that all possible steps have been and would be taken to minimise the risk. Rather, we should be asking whether the possible (undefined) risks arising from the procedure are worth taking given the reasonable certainty that a child would be born with a debilitating illness in the absence of their use. The risk to the future child of being born with such an illness is significant; it is that against which we should be measuring the risks of the technique”

Adding:

“Of course, one could avoid passing on mitochondrial illness by deciding not to reproduce, and adopting. This would provide a perfectly coherent form of parenthood. But the law provides IVF for infertile couples, which indicates that it recognises a right for genetically-related offspring. As such, to insist that people must adopt in order not to pass on certain illnesses seems to discriminate against carriers of mitochondrial illness simply on the basis that they are carriers.”