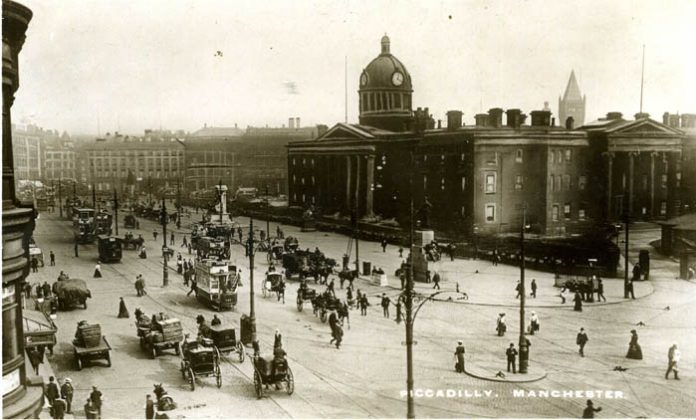

As the controversy continues over the fate of this public space, About Manchester takes a look at its history

The area has been the subject of controversy since records began, a place to punish gossiping women, the site of the town’s Infirmary, the centre point of a space age design for the city and now an experiment in 21st century urban design.

The earliest records of the site refer to its being called Daub Holes, a wet pit at the top of medieval Market Street where quantities of clay for the construction of wattle and daub walls was extracted from the ground.

There are many contemporary sketches of a large lake in the area with depictions of unfortunate women ” punyshement of lewde wemen and scoldes” being dipped by means of the ducking stool, a crude kind of chair balanced in the centre of a pivot and suspended over the water for their misdemeanors. ”

The single stool was installed in 1602, but two decades later it had been joined by five more. The stools were said to have been removed in 1672 as the moat surrounding the nearby Radcliffe Manor House was filled in, but a knot and bridle hung from the door of a Stationers on Market Street into the next century as a reminder for the towns womenfolk to behave.

The ponds survival was assured in the 1750’s when negotiations with the Lord of the Manor over using the land to build the town’s Infirmary contained the proviso that an ornamental lake be built and the land be available for the general public.

The first Infirmary had been opened in 1752 in Shudehill by the surgeon Charles White and the cotton manufacturer Joseph Bancroft. It contained just twelve beds.

White was an interesting character, before he was twenty-four years taking on the founding of the first Infirmary. The medical history of Manchester may well be said to begin with him but in the realms of medical science he is now known as a great obstetrician.

His paper on Treatise on the Management of Pregnant and Lying-in Women published in 1773 was to become a standard work on obstetrics and he was to pioneer almost a hundred years before the existence and role of bacteria in spreading disease was proved by Pasteur, the importance of hygiene were based upon his own experiences.

A blue plaque stands today at the site of his former house in King Street for this man of Manchester elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1761 and who took an active role in the foundation of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society and was one of its first Vice Presidents, whom De Quincey was to call the most eminent surgeon by far in the north of England and during his career, to collect over 300 anatomical specimens, which he gave to St Mary’s Hospital; though most of the material was destroyed in a fire in 1847.

It’s outpatients facility was to attract notoriety in 1819 and much political comment as it treated casualties from the Peterloo massacre brought up in carriages from the site which occurred around a mile away. It had been alleged that the authorities had known that there would be injuries, as prior to the meeting taking place, beds had been emptied at the Infirmary in anticipation of casualties and that one of the injured have been refused treatment, a 25 year old weaver from Saddleworth who had received two head wounds from a sabre, after “refusing to agree with the surgeon’s insistence that “he had had enough of Manchester meetings”.

Many of the casualties avoided the hospital knowing that some of the doctors had loyalist sympathies and feared being turned in by the authorities.

Whilst the popularity of the Infirmary grew, its physical development during the 19th century was to inhibit its development and would eventually force a move away from the centre. There was much debate but eventually the deciding factor was to be money, the offer of £400,000 from the Corporation for the site was too good to refuse and it was decided to build a new hospital at Oxford Road with 500 beds.

In June 1907, a special committee of Manchester’s Corporation met to discuss the use of the Infirmary site and had been charged with considering whether to replace it with an art gallery and public library on the site, as well as being used for other corporation service, one of the proposals was to house some of the council offices in the basement of the building.

With a quarter of the site having been taken up by road widening, the committee was to decide that the new building would take on a smaller space than that vacated by the Infirmary whilst the rest would be used for public gardens.

The outbreak of war delayed any further discussion, by 1916 the site was occupied by a marquee which was used for the recuperation of wounded soldiers.

As the war drew to a close the council voted for the site to be used partially for a new art gallery. The gardens, it seemed, would be returned to the people and work on the sunken gardens began.

Meanwhile a competition to design the new gallery was in progress, it was given a maximum price of £300,000, would be faced with Portland stone, have a prominent clock and be approached in a grandiose manner by a fine flight of stairs. The building would also have space set aside for a memorial hall for the fallen of the Great War

The arguments continued to rumble into the 30’s, the last remaining vestiges of the Infirmary demolished and the whole site opened as a public space, as there was little possibility of the art gallery being built.

Part 2 will bring the story up to date